Supporting Justice

By Meredith Sell

September 2025

S. Lynn Jennings, PhD, LPC-S, never wanted to work with abused children, and she never thought her counseling work would land her in court. But today — nearly 25 years after she got her first job working at Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, a residential program for at-risk youth in Amarillo, Texas, and more than 20 years since she and her husband established their private practice — she has treated more than 2,500 sexually abused children and testified in more than 500 trials as a child’s counselor or as an expert witness.

“I adore my clients and I want them to be OK,” she says, “and if I have to be uncomfortable testifying to help them get the justice and safety that they deserve, then so be it. It is part of my job.”

Throughout the U.S., counselors interact with the justice system in a variety of ways. They work alongside law enforcement to help people in the midst of mental health crises. They conduct fact-finding interviews to learn what victims have experienced or assess the competency of defendants to stand trial. They testify in court, and they provide court-ordered therapy to convicted criminals and parolees with the goal of reducing the risk of re-offense.

All of this work falls under the umbrella of forensic mental health, an area that has been growing as states realize the limits of prison and law enforcement in rehabilitating individuals and responding to mental health episodes. While specifics vary from state to state, counselors everywhere can use their skills in support of justice for victims, perpetrators and communities.

Crisis Response and Civil Commitments

When a person is having a mental health crisis, friends, family or neighbors may call the police. In Mississippi, where Chiquita Long Holmes, CMHT, P-LPC, works, this often resulted in people being arrested and taken to jail when they needed mental health care. Last year, however, the state changed its process so mental health professionals are involved from the beginning.

When a call comes in about a crisis, a crisis response team — usually including a counselor and law enforcement to ensure safety — will travel to the scene and determine if the person needs mental health support and what kind. According to Long Holmes, who is president of Counselors for Social Justice and a mobile crisis emergency response team coordinator, this is where counselors’ skills shine.

“I personally believe that counselors are the most equipped for crisis work,” Long Holmes says. “You understand that first you want to give the person the benefit of their dignity and their humanity, and it’s not just about getting them resources — you are the actual resource.”

The team provides support on the scene and helps connect the person to the care they need. If the person isn’t violent or aggressive but needs inpatient treatment, the crisis response team will help them get to a crisis stabilization unit, and the process for civil commitment (court-ordered inpatient care at a medical institution) will proceed with further evaluations by health care professionals and involvement from the courts.

Interviewing and Assessing Defendants

People of all mental capacities and mental states may interact with the justice system. If they have committed a crime, they need to understand the connection between that crime and what is happening in the courtroom. Counselors like Kisha Norman, PhD, LCMHC, LCAS, conduct forensic evaluations of defendants to determine whether they are competent to stand trial. Norman views this work as a way to make sure people with mental disabilities are treated fairly and get the help they need.

In her evaluations, she assesses whether the person has underlying mental health problems, co-occurring conditions and the developmental capacity to understand why they are going to court and what will happen there. She may also speak with family members and the person’s attorney and gather additional records to make her decision.

“You do have some attorneys who see this as an opportunity to help get their person a leaner sentence … or help them win a case,” she says, “and then you have the defendants who are genuinely developmentally delayed or they have some type of diminished mental capacity, where they truly did not understand the ramifications of their crime.”

Along with determining if defendants can stand trial, she assesses whether they can be rehabilitated. That rehabilitation work aims to help them gain the capacity to understand their crime and its impacts. For those whose mental capacity prevents rehabilitation, the judge decides next steps.

Once she’s made her decision, Norman provides a written report to the court clerk, who passes it to the judge, prosecutor and defense. In it, she shares what she observed in the mental status exam, what history she found, whether the person was always of diminished mental capacity and whether they had previous diagnoses, medical or mental conditions, or substance use.

Some cases turn out in ways she doesn’t expect. In one assessment, the person she evaluated was recovering from a stroke and couldn’t speak. He answered her questions through grunts, nods and gestures. “He had the capacity to stand trial because he understood everything that was going on,” she says.

Forensic Interviews and Counseling of Victims of Abuse

When the police or child protective services (CPS) receive an allegation of child abuse, they set up a forensic interview with the child at a child advocacy center. “You don’t have to be a counselor to do forensic interviewing, but counselors tend to be really good at it,” says Margie Taylor, LPC, assistant clinical professor at Auburn University.

The interview follows a national protocol to avoid asking leading questions and ensure the child describes what they experienced in their own words. The interview is recorded and later used in court, and police and CPS often watch from another room while the interview is taking place. The idea is to limit any re-traumatization by asking the child to tell their story only once. The interview kicks off other work, from relocating the child to a safer home and setting them up with counseling to finding the alleged abuser and embarking on an investigation.

“Sometimes trials don’t happen for a couple of years,” says Jennings, who counsels children in these situations. Before the trial starts, the district attorney may have them rewatch their forensic interview, and the children will often remember more than they initially said.

“They can be like a whistling tea kettle when they get in there and just tell enough to take the pressure off,” Jennings says about the interviews. “Then as they hit different developmental stages, they become safe, and all the things that they were too afraid to tell or that they didn’t even know were wrong, they start processing through that and then more will typically come out.”

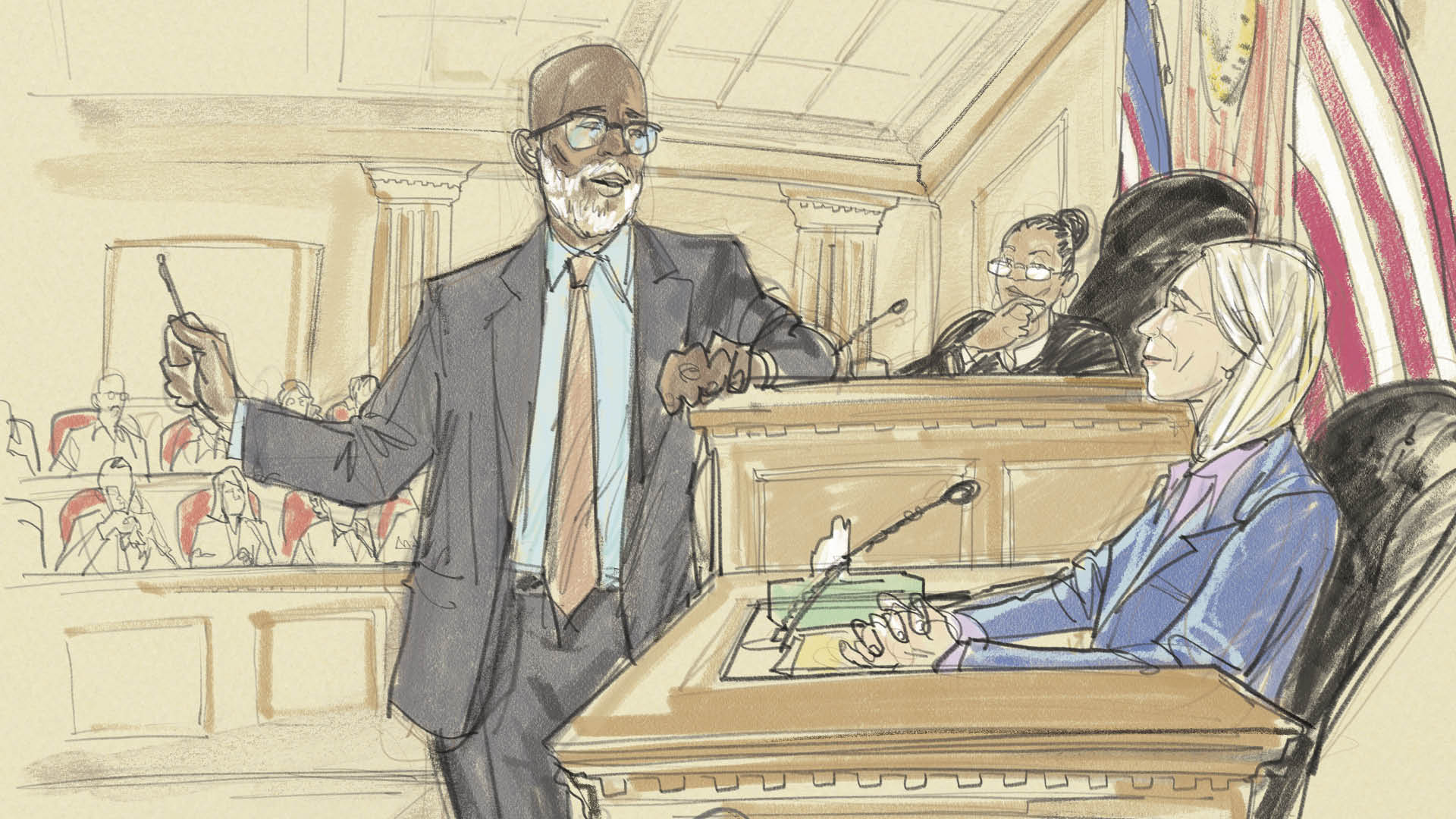

Testifying in Court

Counselors who work with abuse survivors or defendants are often subpoenaed to appear in court — and as Taylor explains, “Law trumps ethics.” Even though counseling ethics call for confidentiality, if a counselor is subpoenaed, they are legally required to appear and provide honest testimony. “You cannot get into trauma work without an expectation of court and trial,” Jennings says.

Sometimes, Jennings is subpoenaed to testify about what she has heard from children in counseling sessions. Sometimes, she’s called as an expert witness. In both scenarios, she prepares for unexpected questions and steels herself against emotions that arise when discussing sensitive topics.

While court appearances are an opportunity to advocate for victims, Jennings warns counselors can go too far and end up hurting their clients’ cases by seeming overly invested.

“You have to go in realizing that your job is to advocate for your experience and your opinion and your observations,” she says. “Your job is not to try that case.”

Still, counselors’ testimony can make a big difference for clients. “Oftentimes, these kids are little, as young as three,” Taylor says. “They need someone to tell their story because they’re not able to do so on the stand.”

Court-Ordered Counseling

Outpatient correctional rehabilitation, where people who are on parole or convicted without prison time are ordered to engage in counseling, has been growing in Ohio as the state has restricted what felonies can send people to state prisons.

“I don’t know if anybody comes out of prison better necessarily. It’s a brutalizing experience,” says Darren Love, LPCC-S, treatment program director at Court Diagnostic & Treatment Center in Toledo, who has worked with former inmates for over three decades. His goal in counseling parolees is to increase their motivation to live a crime-free life while fulfilling court demands for anger management and other types of counseling.

He watches for three factors: impulsivity, or acting without thinking; low insight, which means the person doesn’t understand what they’re doing; and insensitivity to negative feedback. “Some of these guys have been sitting in a principal-type office since they were seven or eight years old,” he says. The negative feedback they get from the justice system, law enforcement and society may register in their minds as the same finger-wagging they received from parents and other authority figures as children, he says.

When someone arrives for their first court-ordered counseling session, Love tries to make the process as pleasant for them as possible. “Your goal is to get them to come back next week because if they don’t come back, you can’t help them,” he says. “Have a pitcher of water, have a dish of candy, chocolate, something. You’re being a bit of a salesman. … Bring them back until they feel like, ‘OK, you care about me.’”

He says it may take someone numerous times to reach the point where they want to change and are ready to accept help. He does his best to meet them where they are. “If you need a high level of validation for your work, you’re not going to make it,” he says. “We just believe that we are making a difference for people. We can’t always predict who.”

This is true for many of these forensic fields. Counselors are brought in at various points — in the midst of crisis, after imprisonment, when abuse allegations are made. Their expertise is key to helping clients and making sure the people and systems who interact with them are informed by the social-emotional understanding that counselors offer. “You’re essentially becoming a public servant,” Norman says. “What you’re doing is going to help somebody else in the future.”