Path to Discovery

By Renée Bacher

May 2024

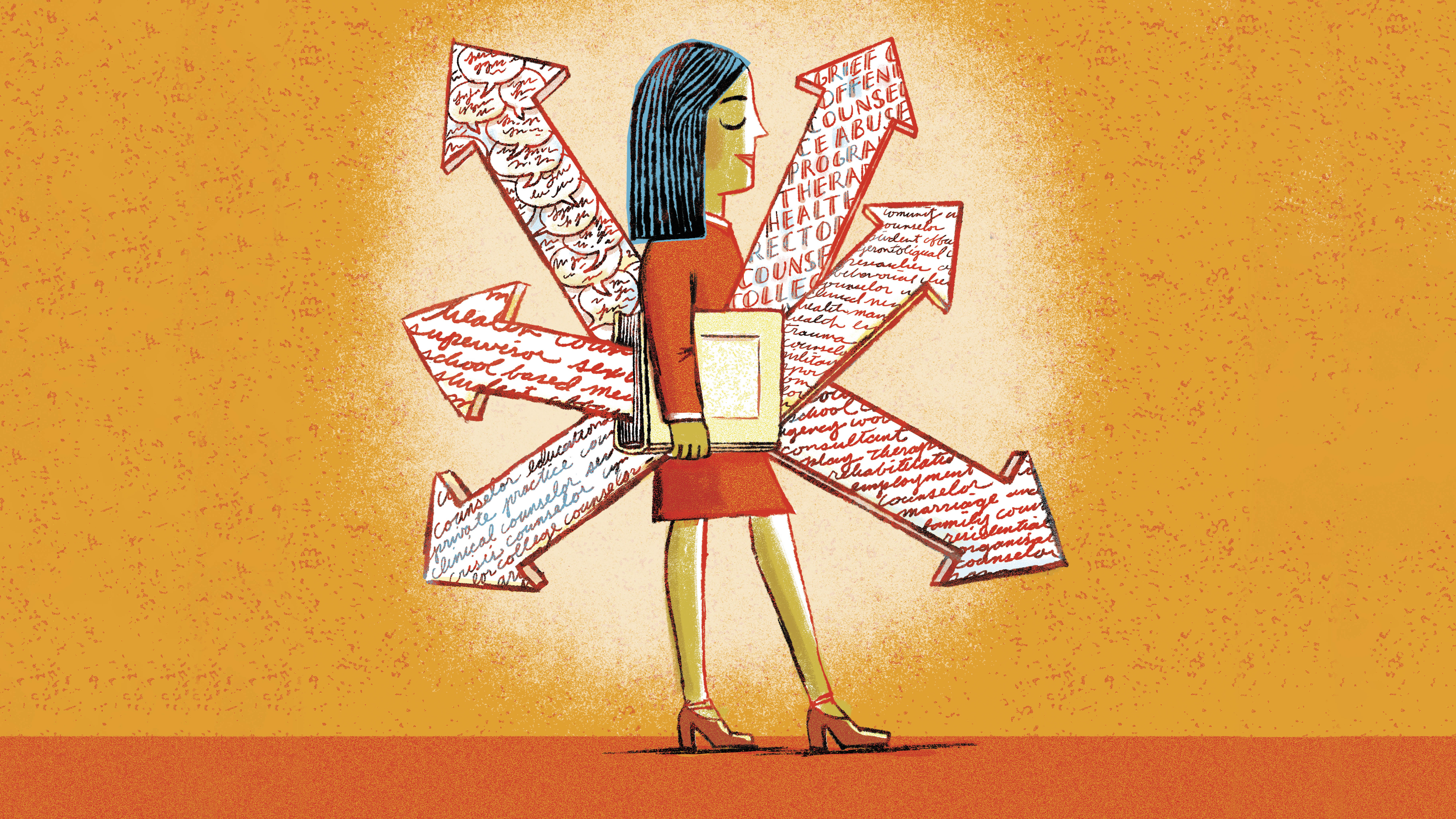

Photo credit: Illustration by Robert Neubecker

While the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a surge in mental health conditions, it also brought them center stage and made a stronger-than-ever case for the importance of treatment and mental well-being initiatives. One result? Unprecedented opportunities for how counselors can use their degrees.

“Counselors can work as practitioners, counselor educators, advocates and facilitators and in a variety of settings, from K–12 schools to universities, hospitals, agencies, private practice, correctional facilities, government and the military,” says Danielle Irving, EdS, LGPC, ACA’s career services specialist.

Furthermore, unique new niches in the profession continue to unfold. One is sports counseling, which can help meet the mental health needs of professional athletes, as well as help them improve performance. “The NFL is now required to have at least one mental health clinician on staff in-house,” Irving says.

Another growth area is integrated health care that places counselors in the same medical offices as physicians to address the psychological aspects of illness. “When you go to the doctor’s office you’re typically focused on your physical health,” Irving says. “But now doctors are making sure they’re integrating health care and having professional counselors within that space because at times the physical illness one experiences is going to have an impact on their mental health.”

And we know the reverse is also true: Mental health can affect physical health as well. “It is important to have a holistic approach that includes professional collaboration and communication to best serve our clients,” Irving says.

Employment in selected occupations that provide mental health services has grown in the past decade. It is predicted to far exceed the 3% average growth for all occupations from 2022 to 2032, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Projected growth for substance use, behavioral disorder and mental health counselors is 18%, with 42,000 openings per year expected from 2022 to 2032. And according to Irving, children’s mental health post-pandemic is a particular area of demand, with school-based mental health counselors needed to respond to the crisis.

Today’s counseling graduates can thrive in a wide variety of settings, ranging from traditional private practices and agency work to solely conducting assessments or trainings or working with corporations and associations. Here, we feature a few paths ACA members have taken to find fulfillment and to make a difference in their careers.

Omar Troutman, PhD, LPC

Private practice and assistant professor

Lexington, South Carolina

Near the end of a 12-year career in restaurant management, Omar Troutman, PhD, LPC, had an epiphany: “I remember feeling that my calling was to help people and the restaurant I was working in was a business that wasn’t helping anybody,” he says. “If anything, they were trying to figure out how to get the most they could out of as many people as possible.”

Troutman’s first bachelor’s degree was in business, so when he left the restaurant world, he returned to college to earn a second bachelor’s degree, this time in psychology. A natural next step would be to pursue a doctorate in psychology. However, Troutman had spoken with counseling professors who had explained the difference between psychology and counseling: Counselors are the ones on the front lines doing the work. Psychologists do the testing.

“I felt the only way I could influence and help communities was if I was in it, so that’s what I did,” he says. “Directly after my BA was done, I went straight into the EdS counseling program, and I leaned into that hard.”

In 2006, as Troutman was starting graduate school, there was a spike in suicide rates for LGBTQIA+ youth. As a cisgender gay male, Troutman felt inspired to support this community. “We were losing too many of our young folks in the community, and there was no reason for that,” he says. “I had identified my population.”

Every project he did in graduate school was related to this population, and because he had always wanted to make large-scale change, he decided to pursue a doctorate in counseling with the ultimate goal of teaching.

“As a practitioner, you’re seeing maybe five to six people per day for four to five days per week. But when you teach, you have about 12 people in every class, and if you can get them inspired, then they can go do the work that will continue impacting the field, in addition to adding to the knowledge base that is counseling and psychotherapy.”

After obtaining his doctorate from the University of South Carolina, where he had done all his postgraduate work, Troutman spent eight years working in community mental health centers. He developed an LGBTQIA+ cultural competency training that he delivered to mental health professionals across the state before beginning to teach online as an adjunct for Walden University. “I loved teaching, I loved the students, and I loved online learning,” he says.

Troutman continues to teach online, but now he is working full time as an assistant professor at The Chicago School, in addition to maintaining a private practice that focuses on the LGBTQIA+ community. “You can go wherever you want in this field,” he says. “It’s just what you’re willing to do and experience and who you’re willing to help.”

Evelyn Iraheta, EdD, LPC, LCPC

Private practice and school counselor

Washington, D.C.

As a counselor, Evelyn Iraheta, EdD, LPC, LCPC, is able to connect with the immigrant community she serves in ways that many others cannot. Arriving in the U.S. from El Salvador at age 14 with her younger siblings, Iraheta reunited with their mother, whom they had not seen in seven years. The siblings went on to become five of seven children who would live in a two-bedroom apartment with their mother and stepfather.

“I used to study in the bathroom,” Iraheta says. It was the only place in the apartment that was quiet and where she could be alone behind a door.

Iraheta was the studious one in the family and the only one that would end up attending college (and beyond). But it wasn’t easy. In high school, without access to a computer for schoolwork, she had to rely on the library. And although she was accepted to Hampshire College in Massachusetts with a partial scholarship, she struggled to afford staying enrolled.

“My mother was able to give me $300 for the four years, and that was all. The rest I had to earn myself while going to school,” she says. “The main problem was that the dormitories closed during school vacations, and I had nowhere to go and it was too expensive to get home to D.C.”

To ease her struggles a bit, Iraheta transferred to Hood College in Frederick, Maryland, which was an easy, much shorter bus ride home on school vacations. She completed her bachelor’s degree in three years while working whenever she had a spare moment. “I had AP credits from high school, which helped,” she adds.

After college, Iraheta considered counseling while working as an academic adviser with under-resourced youth at a nonprofit. “I noticed how students were struggling with an array of issues that needed specialized attention,” she says. “Of course, I tried my best, and my colleagues did too.” But she knew they needed more comprehensive services. She researched careers, and counseling came up as an on-demand field.

Iraheta now has a master’s degree in counseling and a doctorate in counselor education and supervision. She has her own small private practice and works as a school counselor at Columbia Heights Educational Campus in Washington, D.C. She has extensive experience providing culturally and trauma-based individual, group and family psychotherapy to low-income families and diverse client populations in English and Spanish.

Students open up to Iraheta about their struggles, she believes, because they realize she understands them firsthand. “They see that if I was able to overcome so much and still go to college and beyond,” she says, “they can endure their challenges, too.”

Sharon Givens, PhD, LPC, LCMHC

Private practice and owner of a training and professional development company

Columbia, South Carolina

After earning a master’s degree in counseling, Sharon Givens, PhD, LPC, LCMHC, worked in substance use counseling and hospital psychiatric care. But she soon felt defeated. “I was eager to help and would really pour my all into clients,” she says, “but about six months later, they would show up again.”

Further disheartening, the agencies she worked with were “very much for-profit.” She soon realized that ethically, her values did not align with theirs. Her personal mission, she says, was to help others, whereas theirs seemed to be the bottom line.

In search of a better fit, Givens earned a second master’s degree. This time, she focused on adult education and training. She went to work for a state agency creating professional development programs for teachers and administrators. She conducted personality assessments and helped clients learn more about themselves to enhance both their performance and their own personal fulfillment in their careers.

While working and pursuing a doctorate in clinical mental health counseling with a focus on curriculum and counseling instruction, Givens also became trained as a career development facilitator. She taught part time in a counseling program, where she realized she enjoyed training a lot more than academia.

Givens took what she describes as “a huge leap of faith” — before getting her license, she left her job, opened a private practice and started seeing clients. That was 14 years ago, and she hasn’t looked back.

In addition to running her private practice, she owns a training and professional development company, Training Visions, which focuses on wellness, resilience and self-care. “I do a lot of workshops and retreats,” she says. “One of my favorite things is marrying training with mental health.”

Recently, Givens launched a podcast called Between Sessions with Dr. Sharon, covering topics such as career satisfaction and personality, workplace trauma, and living a healthier life through personal development.

“I am constantly looking at ways to integrate mental health counseling and career counseling,” she says. “It’s actually not very difficult because many times when people are struggling with mental health issues, they’re struggling with work as well.”

Gregory K. Moffatt, PhD, LPC

Consultant, professor and college dean

Atlanta

It’s difficult to put a finger on what it is exactly that Gregory K. Moffatt, PhD, LPC, does with his counseling degrees because he does so many things. And even as he approaches retirement age, he doesn’t want to stop doing them.

From private practice to consulting with law enforcement and the FBI on criminal profiling, to writing columns and books, appearing in documentaries and serving as dean of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Point University in West Point, Georgia, Moffatt is certainly never bored. Retirement, he worries, despite his wife’s protests, might be boring.

It all began for Moffatt after a less-than-idyllic childhood navigating poverty and abuse. “I wanted to make sure I helped children to have a better road than I had,” he says. “I didn’t have a childhood, basically. I was paying my own doctor bills at 12 and left home at 15. I never got to be a kid.”

Although counseling children wasn’t offered in his graduate program, Moffatt pursued it after getting his degree. He advises his students today to get their master’s degree and then polish their skills through continuing education and professional organizations. He still treats children, especially those in foster care, dealing with trauma from sexual or physical abuse. And he’s driven to address their critical needs, noting the pandemic brought a flood of youth mental health crises and that there are limited options for help.

In addition, Moffatt’s articles on predicting violent behavior opened unexpected doors. He was recruited to teach profiling techniques at the FBI Academy to agents working murder cases, a role he would fill for a decade.

“Profiling combines statistics, psychology and investigative savvy to guide agents on where to focus,” he says. “It was an honor to bring my counseling skills to advance their approach.”

Through his work with law enforcement, Moffatt began to be approached to consult for television and movies. About 10 years ago, he was driving when his cellphone rang. It was the actor and filmmaker Tyler Perry, who needed coaching for a role where he would play a profiler in the film Alex Cross.

“I rarely gave out that number,” Moffatt says. “I didn’t know who he was and hadn’t seen his movies, so I thought somebody was pulling my leg. It was really funny.”

Moffatt’s motto these days is that when it stops being fun, that’s when he will retire. So far, that’s not looking likely any time soon.